They say that in the summer of 1792, something unspeakable stirred in the woods around Cusago, a quiet town just beyond Milan. Locals began to whisper of a creature that came out only at night — La Bestia di Cusago, The Beast of Cusago.

What followed was not rumor, but record. In early July, a ten-year-old boy named Giuseppe Antonio Gaudenzio vanished while looking for a stray cow near the forest. The next morning, they found him — what was left of him — half-devoured, his clothes soaked in blood. Within days, panic had spread through the countryside. In Limbiate, children guarding cattle were attacked; those who climbed trees watched helplessly as the creature dragged away eight-year-old Carlo Oca. Then came Giuseppina Saracchi, ambushed on a country road while walking with her sister. Three children, gone — and fear now had a name.

Descriptions of the Beast varied, but all were terrifying. Some swore it had the head of a boar and the body of a dog, as large as a bull, its back streaked with reddish hair. Others spoke of horse-like ears, thin limbs ending in clawed paws, a tail long and curled. Hunters claimed their rifles jammed when they aimed, and that even the bravest among them trembled, unable to pull the trigger. The creature seemed untouchable — almost unnatural.

Desperate, the authorities offered fifty zecchini — a small fortune — to anyone who could bring it down. Pits were dug, bait animals tied to stakes, and armed men filled the fields. By late September, they declared victory: a wolf had fallen into a trap near Cascina Pobbia. Its carcass was displayed, then sent to the Natural History Museum in Pavia as proof that the terror was over.

But those who had seen the real Beast never believed it. What they remembered was something far larger, far stranger than any wolf. And when, years later, the stuffed body vanished from the museum without explanation, the doubts only deepened.

Some historians say it was simply a starving animal, driven mad by hunger. Others compare it to the legendary Beast of Gévaudan — a predator born of fear as much as flesh. Yet for those who still live in the shadow of Cusago’s woods, the legend endures. On cold nights, when the fog drifts low over the fields, they claim to hear a growl in the distance — faint, guttural, unmistakable.

They call it the Devil Wolf, the lupo del diavolo.

And every year, when summer turns to autumn and the nights grow long, the people of Cusago remember the dark season when something walked among them — something that never truly went away.

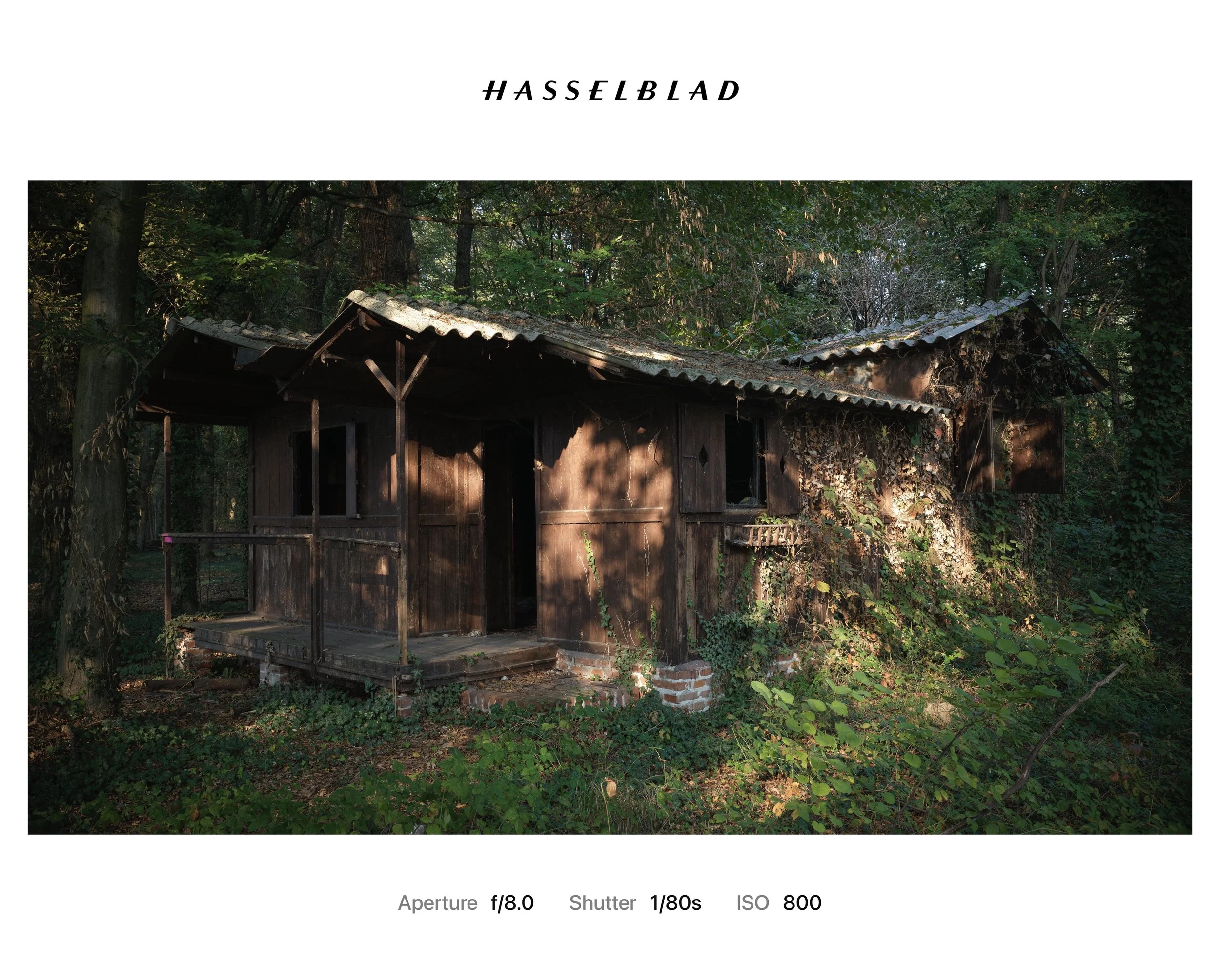

Today, that same forest is sealed off, under the control of the Demanio, officially closed to the public. But a few weeks ago, curiosity got the better of me. I went in anyway. Deep among the trees, we found an abandoned lodge, silent and forgotten, its windows shattered, its roof half-swallowed by vines. The air felt heavy — still, but alive somehow. I wasn’t alone; a friend had come with me. And yet, the whole time, I kept trying to guess where the nearby highway was — just to stay oriented, in case I had to run out quickly, and to make sure I didn’t lose myself in there.

They call it the Devil Wolf, the lupo del diavolo.

And standing there, with the woods pressing in from all sides, I understood why.